Diving Into The Forest

Nature, awareness, deceleration, meditation: ‘shinrin-yoku’, meaning ‘bathing in the forest’, is a recognised treatment in Japan. It’s also spreading to Germany as a by-product of the general mindfulness trend. Why is it so popular? Accompanied by two guides, partners Carlos Ponte and Emma Wisser, we headed off to the Mangfall Valley, close to Munich, to test the waters and discover what this activity is all about. Between the trees and wet earth, we learned something about the healing qualities of the forest — and about ourselves as well.

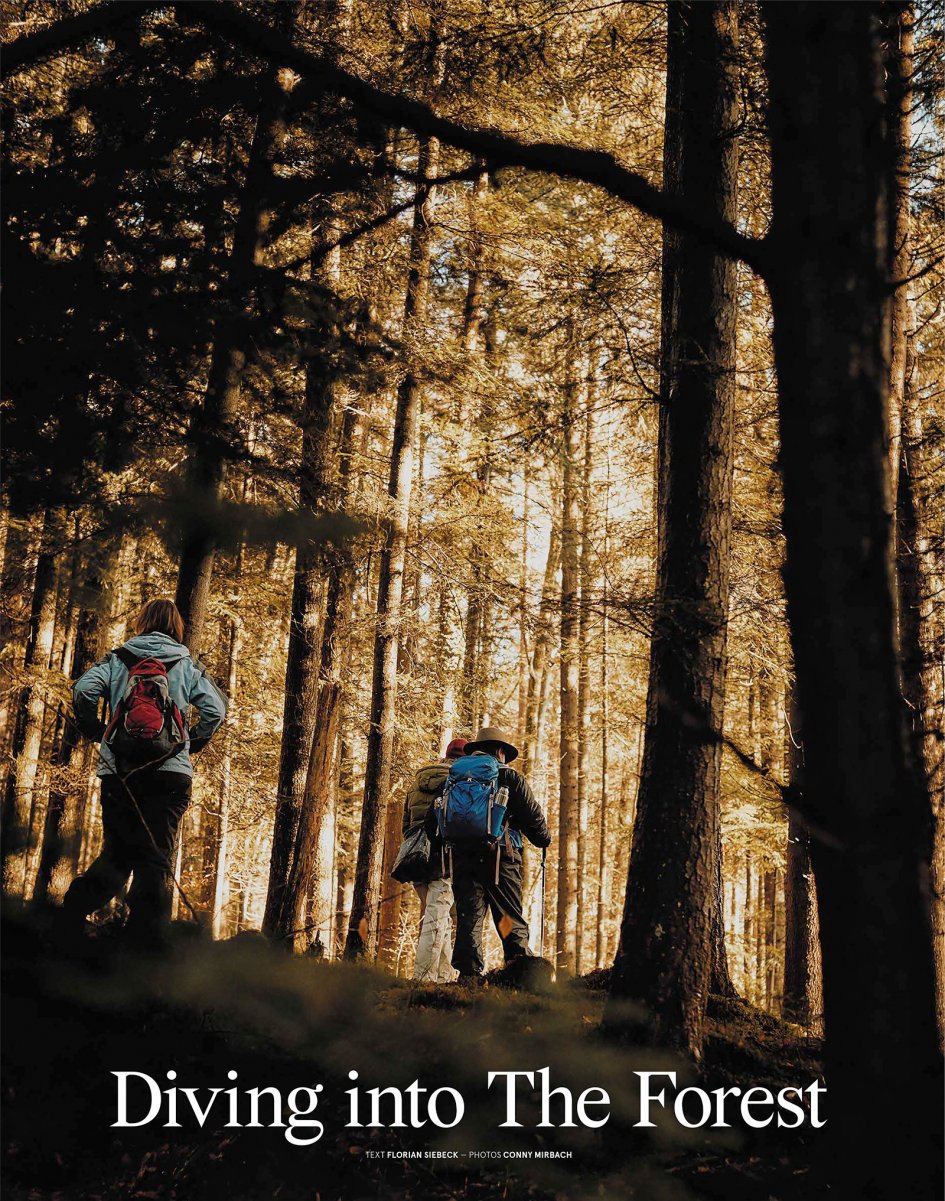

This particular day in December has a different quality to it somehow. It feels more like the tentative awakening of spring: the air is clear and the weather mild, as the sun glances gently through the treetops. Here in Upper Bavaria’s Mangfall Valley, the forest is still surprisingly lush. There has hardly been any deforestation in the water basin around Munich, and the woodlands are left largely to their own devices. That’s why everything looks so untouched — the way they were seen by the German poets of the early Romantic period, who perceived the forest as a place of longing and emotion.

We have come to experience the woods with all of our senses. To grow closer to ourselves, just a little. shinrin-yoku is the name of the Japanese method for this: bathing in the forest. ‘In a figurative sense, it means absorbing the forest, enjoying it, placing oneself in a direct relationship with nature, the trees, wind, light, and soil,’ says Emma Wisser. She is leading us through the woods with her partner Carlos Ponte. Bathing in the forest is an officially recognised form of therapy in Japan and the United States — but shinrin-yoku is still largely unknown here in Germany. Is it just a walk? Is it going to be strenuous? ‘Bathing in the forest is not athletic at all. But neither is it a walk. It’s actually more of a sojourn. We are in the forest, with the forest, and can allow ourselves to be surprised by what happens. How we feel, what we sense — the responses are always very personal.’

Shinrin-yoku was introduced by Japan’s Ministry of Agriculture in the early 1980s. It started out as a marketing campaign: the idea was to encourage people to appreciate the forest, to recognise its beneficial effects, and to stop perceiving it merely as an economic resource. The ministry poured millions into researching the forest and its salubrious effects. Soon afterwards, the first centre for forest therapy opened its doors; these days, medical students at Japanese universities can even qualify as specialists in forest medicine. Here in Germany, forests cover almost a third of the land, making it one of the most wood-laden countries in the European Union. Now we are seeing the emergence of medicinal forests, especially in the rich woodlands of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania. Across both countries, it is said that the forest can alleviate physical symptoms and provide relief from emotional afflictions.

So here we are, ready to dive into the woods at the gates to Munich. Carlos and Emma have organised these tours for two years now, twice a week in summer and by appointment in winter. What brought them together was meditation, or more precisely, an app. Originally from Argentina, Carlos had worked as an IT forensics specialist in Canada, seven days a week, for decades. ‘I had no life left,’ says Carlos — so he took up meditation. He discovered a meditation app that allowed him to communicate with like-minded people. And he kept coming across a photo of Emma, who runs a practice for mindfulness and self-compassion in Munich. Carlos and Emma started messaging, then talking on the phone, eventually arranging a date to cook together. When they discovered that they share the same birthday, Carlos dropped everything, sold his house in Calgary, and moved to Weyarn in Bavaria. ‘We decided to work together on mindfulness, with a holiday component. European vacations with a mindfulness twist. Here we have space, peace, and nature around us,’ explains Carlos.

Before setting off, we fortify ourselves with some minestrone that Carlos made. It’s a half-hour walk from their home, across the fields and through the forest. We stop by a small waterhole, stretch, and do a few qigong exercises. Carlos tells us that the lungs contain half a litre of air that is hardly exchanged when we breathe normally. ‘So now let’s get rid of this Munich air!’ We take deep breaths in and out.

To experience the woods, we need to open our spirits, dispel nagging doubts, and welcome nature in. ‘It is also about becoming aware of a particular quality of the forest,’ says Emma. ‘There are no rules. It beckons everyone in. What would happen if we treated ourselves the same way that the forest does?’ Carlos pauses between two trees. The portal to another world lies right here, he says: a world in which the spirit only perceives the forest, the here and now. The snapping of twiglets beneath the soft, damp humus, the tiny clovers eagerly stretching their leaves to the light. We are told to explore our surroundings by ourselves for a few minutes. ‘Introduce yourself to the forest’ is Carlos’ way of putting it. ‘Let nature back into you. Disconnect.’

We experience the forest like children, tracing our hands across the bark and the lush verdant moss, breathing the clean air, and gazing up as the treetops sway in the wind. Far away we hear the burbling creek at the base of the valley as our eyes delight at the manifold colours, still resplendent in the wintery woods: rusty red, purple, green, yellow. Hecticness and haste melt away. ‘Just be there, just feel,’ says Emma. ‘And don’t be shy: perhaps we won’t chat all the time, but there is no need to walk in silence.’ One of those quieter moments comes when we reach the banks and each of us takes a stick onto which we project our anxieties. Then we lob them into the water, letting go of the negative thoughts, just for one day. ‘It’s surprising, but the groups we accompany tend to bond,’ muses Carlos. Afterwards, we wash our hands and faces in the ice-cold water.

Carlos tells us that the couple were once visited by a family from Brooklyn. Their seven-year-old daughter had never walked more than a few metres at home. The parents had given up, thought Carlos, who then said, ‘Let’s just see how far we get.’ The child explored the forest transfixed, walked the whole path, six kilometres, without complaining once. Her parents were lost for words. What is this magic at play in the forest? Why does it slow us down? Is it a journey back to the primordial days of human existence?

Scientists around the world are investigating the psychological and physiological effects of shinrin-yoku. Their work began in the 1980s, when biologist Edward O. Wilson proposed the biophilia hypothesis, which describes the innate love that humans feel for all forms of life around them. It is part of our DNA — the result of an evolutionary process spanning millions of years. Swedish scientist Roger Ulrich discovered that hospital patients recover faster if there are trees outside their windows. And Qing Li, a Japanese researcher who has penned dozens of studies on the medicinal effects of the forest, determined that our blood pressure, cortisol levels (stress hormone), and heartbeat drop noticeably after only an hour in the woods.

The Japanese believe that forest air extends life. It’s true: strolls through woodlands strengthen our cardiovascular systems and boost our natural defences. Scientists at the Nippon Medical School have found that white blood cell activity can rise by as much as 50 percent after a few hours spent in the forest. Not only do these cells fight germs but they also help to prevent cancer. Qing Li believes that terpenes — messenger substances in trees — are responsible for this effect. Trees use these volatile organic compounds, known as phytoncides, to fight off pests and diseases. Scientists in Germany are now also investigating whether our forests, with their significantly different set of trees compared to Japan — oak and beech trees, instead of cedar and larch — could have similar effects.

Carlos digs his hands deep into the wet foliage. He holds it up to our noses. Everyone agrees that the fresh forest floor smells divine — although no one can explain precisely why. Is it the messenger substances? Memories of carefree childhood days? Although it has been demonstrated that inhaling phytoncides produces a calming effect, some scientists believe that the bouquet of aromas comprising terpenes, essential oils, and moist soil primarily reminds us of pleasant memories of ambling through trees. Collecting mushrooms with the family. Excursions with friends.

Our three hours in the forest are all about experiencing nature with all of our senses, discovering traces emblematic of our personal narratives. We stop in a glade. The sun sends tendrils of light across the fresh moss, and the scenery appears as perfect as a painting. We close our eyes and listen to the rest of our senses. We feel, hear, smell, and taste the forest. Clutching warm mugs of spruce needle tea, we set off to find a tree that especially appeals to each of us. ‘Tea with a tree’ is Emma’s name for it. And it’s entirely up to us whether we hug the tree, talk with it, gaze at it, or lean against its trunk.

‘We are trying to find a balance between an academic and an esoteric approach. Mindfulness enhances the effects of the forest. It’s humbling to see that we’re making a difference in people’s lives, one at a time. It is rewarding, and a big responsibility.’ Carlos recently returned from Japan, where he shared ideas about shinrin-yoku with the prestigious researcher Yoshifumi Miyazaki, and took time to visit the Akasawa National Recreational Forest, to which around five million Japanese flock every year. Forests play a significant role in Japanese history and mythology.

Not only is this nature-based mindfulness a blessing for the spirit — it’s also one for personal growth. Towards the end of our walk, Carlos gives us a handout with tips on how to incorporate shinrin-yoku into everyday life — in the green lungs of the city — to take a little break from the rationalism, hedonism, and materialism of urban existence. ‘For 99.9 percent of history, human beings lived in nature,’ says Emma. And even though around 1,300 square metres of forest would theoretically be available to each person in Germany, hardly any of us make use of it. ‘We are all part of nature, even if we don’t feel that way,’ says Carlos before we leave the woods behind. ‘This is not only a forest. This is home.’

Erschienen in Companion Magazine am 24. Januar 2019.